My favourite thing to do is to sit and watch wild animals. I always wonder what they’re doing and why? – which, in a roundabout way, has led to my current collaboration with Botswana Predator Conservation.I’m investigating African wild dog social behaviour and movement ecology in the hopes of better understanding pack movements and the social dynamics that help explain them. The more we learn about wild dog movement behaviour, the better our chances of informing conservation and wildlife management strategies to manage,even manipulate, pack movements away from conflict areas. I’d love to gather all my data by hanging out with and directly observing our well-known study area packs. However, that’s not possible all the time. In order to collect data on more cryptic (difficult to observe) behaviours and long-distance movements,I aim to supplement my binoculars and notebook with a range of wildlife telemetry equipment that use new technologies and allow me to collect some of these behavioural records remotely.

My broad aim in using such ‘conservation technologies’is to investigate the influence of predation risk on African wild dog behaviours, I am specifically interested in their responses (in terms of their moving from their den sites) to naturally-occurring lion calls (because lions are their main predators). To achieve this, I will be combining bio-logging, bio-acoustic and camera trap technologies to record these movements during the denning season. When the dogs have pups in a den, they return to the den after hunting to feed and look after the pups. This differs from the rest of the year when a pack travels widely across their territory. This relatively predictable behaviour makes it possible to position data recording equipment near den sites to record the behaviours of interest with greater data capture reliability. Using these technologies minimizes the risk of human disturbance possibly influencing their behaviour and also allows behaviours to be recorded during times (and in locations) that are otherwise difficult with direct observation, including for example, at night, and when animals are on the move and cannot be followed easily, and for longer periods of time than is possible with direct observation.

Helping deploy a GPS collar on Ebra,the dominant male in Mma Barbies pack

But what tech will be most useful?

Global Positioning System (GPS) collars

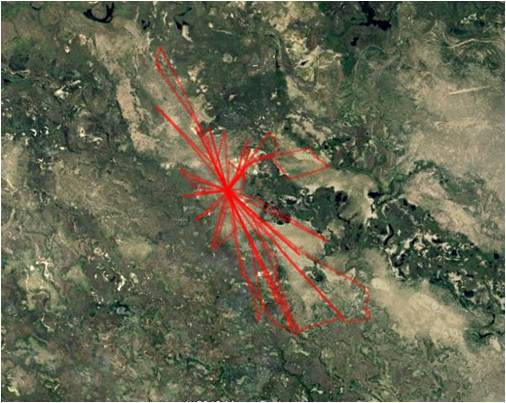

I will use one GPS collar per pack to record movement behaviour such as speed and direction of travel during the dogs’ morning hunting forays. For group-living animals that move as a cohesive group, like African wild dogs, it’s possible to use the track of a single dog to represent the pack’s movement. Collars can be scheduled to take GPS fixes of the dogs’ location every five minutes during the morning hunting period, but a lot of work goes into building the collars themselves. These need to house and power a GPS unit to collect the movement data, a VHF ‘pinger’ so that the pack can be located by tracking on the ground, and batteries to power both of these. For GPS devices deployed on free ranging animals like these collars, there are important ethical and design considerations in terms of size, weight, visual appearance, and attachment/removal methods. Fortunately, with new technologies, these have all decreased in size and weight since their development in the 1990s.

Once we have deployed one of these collars we can begin remotely downloading the GPS movement data during our visits to the den.The collars I use are designed to drop off unassisted after a number of months when the cotton fabric used to fasten the collar degrades and comes apart.

Acoustic recorders

I will also use arrays of acoustic recorders around each dog den to record naturally-occurring (especially nocturnal)lion calls, as well as vocalizations of prey species and dog alarm vocalisations. These will be strapped to trees high enough (hopefully) to keep them out of reach of potentially destructive animals such as hyenas, and configured to start and stop recording at specific times (e.g.,overnight) and an array of multiple recorders can be used to calculate the bearing and distance of target sounds (for example lion calls) in a technique known as localisation.

GPS tracks collected by Ebra’s collar showingpack movements to and from the den.

Left: Home-made camouflage design painted on the housings of my acoustic recorders.Right: Spectrogram of a lion call recorded by one of the units.

Camera traps

Finally, I will deploy trail cameras, in research known as camera traps, that capture images overnight. Triggered by movement these should capture behaviours of dogs nearby, such as vigilance behaviour that might be in response to predator sounds. Camera traps have only fairly recently started being used to study animal behavior, as opposed to just recording presence of certain species. Anti-predator vigilance behaviour is an indicator of perceived predation threat. So, I will use photos and videos from camera traps to quantify behaviours that reflect this perception.

Challenges remain …

Continuing developments in various technologies like GPS collars, acoustic recorders and camera traps are enabling smaller, lighter and cheaper units with longer battery life, and therefore these are becoming more useful for conservation field research. However, challenges remain! Batteries must constantly be charged, which can be tricky in remote areas where we rely on limited generator and solar power. Time is a factor. Time not spent watching animals directly must nonetheless be committed to process the recordings from memory cards and GPS downloads. The hours of recorded files must be stored and later reviewed from multi-terabyte hard drives. We occasionally have to rescue acoustic recorders and cameras from the dirt after an elephants found it interesting enough to vandalize.

Left: One of the camera traps.Right: An example of a camera trapimage of wild dog vigilance behaviour at night (this is the dominant female inthe Apoka pack).

Despite these challenges I expect using new technologies will ultimately be rewarding, by allowing me to investigate the fine-scale behavioural responses of Wild dogs to predation risk with a level of precision and detail that would otherwise be impossible. And hopefully provide insight into the effects of other large predators on African wild dog behaviour. I doubt I’ll ever want to give up direct behavioural observations, because spending time with free-ranging wildlife is such an incredible privilege. But using technologies tied in with my direct observational data on the dogs’ social behaviour will no doubt reveal a more detailed picture of the movements and social dynamics of this iconic and endangered species.

(Lucy Ransome’s project is supported by a grant from the National Geographic Society)

Written by

Lucy Ransome

Dive straight into the feedback!Login below and you can start commenting using your own user instantly